Finance Franchise

Introduction

Banks are ubiquitous nowadays. We can’t walk in a city without seeing a bank branch every few minutes. We can hardly afford to buy a new vehicle without a loan from one of them, let alone buy a property. If we are workers, we receive our salary in a digtal account. We pay our taxes with the help of one of these banks. These are just to name a few.

Nevertheless, it might happen to you to wonder how the banks actually work. We all have a notion, even though vague, about how they work, but from where did we get this image? Is it compatible with reality? And why does it matter to know how they work?

In this article, we are going to learn how the banks work and how they don’t! Then we ponder about the reason behind their existence and whether this existence rationale is in line with the banks’ performance.

How Do Banks Work?

I don’t know about your first impression, but my first impression of banks was shaped while watching the Lucky Luke cartoon! A bank in that world was a building with no ornaments, an old man with a pair of sleeve graters, and a safe! The safe was for keeping the deposits, i.e., local people’s savings, that either would be given to a borrower as a loan or robbed by some sinister thieves!

But this must not be the case in reality, must it? Don’t worry if you are not sure how the private banks work; there is no consensus among the professional economists about it. In the economics literature, there are three contending theories about how private banks work, especially how they provide loans, and what their role is. I will guide you through these theories and their implications, in addition to showing which one matches reality.

The first theory is very similar to the story of the banks in the Wild West! In this theory, banks are intermediary agents connecting those who have money to save to those who have an idea but are short of money to realize it. The main role of the banks, then, is to attract deposits and allocate them to the most profitable and least risky investors. This model has some very important implications. The main one is that loan provision is bounded by the amount of available deposits, and the deposits, the private funds, must be available in the first place before a loan is issued. A policy implication then is that, in order to increase private investment, saving must be encouraged.Therefore, not only is money provided outside of the banking system, but saving also drives investment. This is Daltons’ theory, sorry, I mean the financial intermediation theory or the credit intermediation model.

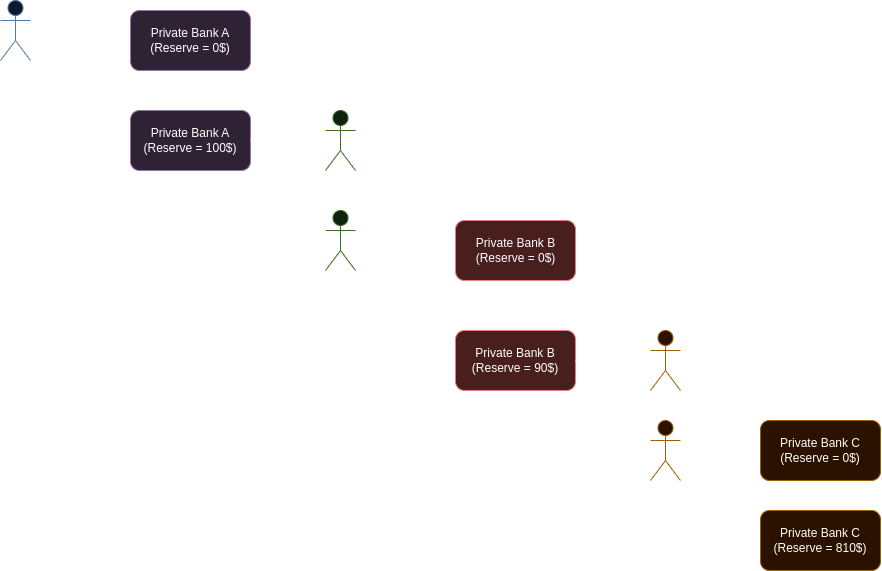

Nevertheless, why not consult an economics textbook to understand how private banks work? The textbooks must be correct, right? Let’s pick the most re-published and famous one: Macroeconomics by Gregory Mankiw. In the banking chapter of this textbook(Mankiw 2013), we can learn that private banks work under the fractional-reserve banking system. The story starts with a saver who wants to deposit their savings at a bank. However, unlike the credit intermediation theory, the deposit-taking bank figures out that they don’t want to keep all the deposits all the time. Anyway, how likely is it to have all the savers asking for their deposits at the same time? It is better to keep a fraction of the deposits and lend out the rest. The part that is kept is called the reserve, and the ratio of the reserve over the total deposits is called the reserve ratio. Why not lend out all the deposits? Well, the central bank or any other regulator has set this reserve ratio as a control measure to reduce the risk of a money shortage in case many depositors ask for their money. That reserve is kept at the central bank and is part of the narrow money, while the deposits are composed of the broad money or money supply. 1 The following plot portrays a few rounds of loan issuance under this theory.

As you can see, in the above model, through an initial \(1000\$\) deposit and in two lending contracts the banking system increased the deposits to a total sum of \(2710\$\)2. In contrast to the previous model, the banking system can create money through multiplying the initial deposit. This is why the model is also named credit-multiplication model(Hockett and Omarova 2016)

As you can see, in the above model, through an initial \(1000\$\) deposit and in two lending contracts the banking system increased the deposits to a total sum of \(2710\$\)2. In contrast to the previous model, the banking system can create money through multiplying the initial deposit. This is why the model is also named credit-multiplication model(Hockett and Omarova 2016)

This model is similar to the first model in that deposits drive loans, i.e., without any deposit at a bank, the bank cannot issue any loan. In both models, lending is restricted by the already-accumulated deposits, and loans come from such deposits. Therefore, savings drive investments.

he role of the central bank is minimal in this model, as it sets the reserve ratio. By changing the reserve ratio, the central bank can control and determine the money supply, i.e., total deposits. For instance, by increasing the reserve ratio from 0.1 to 0.2, the aggregate deposits can be reduced to \(2440\$\)

However, the above model does not match the empirical research(Werner 2014), central banks explanationsIhrig et al. (2021) or even the private banks (Bundesbank 2017) themselves!

How does private baking work, according to these sources? This is the third theory of banking: the credit-generation model or credit-creation theory. In this model, private banks issue loans out of thin air. They are not bound by the available deposits or reserves3. The loan officer does not check the reserve position of the bank or the amount of available deposits when they want to issue a loan. What do they check? Whether the person requesting the loan is creditworthy and whether the loan is profitable. 4 Can a bank create unlimited loans then? No. Besides the profit and risk limitations, there is an imposed restriction by the central bank or other regulatory/supervisory agents based on the capital adequacy ratio (CAR). This ratio is the proportion of the capital of the bank, i.e., what remains out of the assets if they pay back their liabilities, over their risk-weighted assets. Since not all assets are equally risky, their price is considered from the perspective of their risk. The higher the risk, the lower the CAR. The higher the capital, the higher the CAR. Private banks are supposed to meet a minimum CAR, let’s say 13%. If they violate this ratio, they have to pay penalties, so this restriction also has a business side.

What are the implications of this model? Savings do not drive investments. We do not need to encourage saving if we want to increase investment, and quite contraryly, we need to encourage spending. Moreover, the central banks do not control the aggregate deposits. They don’t have the power to do so. They can influence loan creation, but not control it. What about the reserve ratio? Some countries have a minimum required reserve ratio, but that is not binding on banks to issue loans. Meeting that minimum reserve is mainly for intra-bank transactions, and a loan-issuer can always meet that requirement after issuing a loan, if needed. The central bank guarantees the availability of the reserve in case of the bank’s shortage. And that leads to the next point. Does it mean that private banks can create unlimited amounts of deposits? No. The private banks are limited by their profitability and risk. They are limited by the number of creditworthy and profitable clients, the capital adequacy ratio demanded by the regulators, and the cost of funding.

| model | can increase money supply | deposit-loan causal sequence | what limits loan-issuance | how money supply can be controlled | what determines money supply | how to stimulate loan issuance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| credit intermediation | no | deposit drives loan | initial deposit, creditworthiness, and profitability | money supply is fixed | the initial deposit | - |

| credit-multiplication (fractional reserve banking) | yes, but it needs at least two private banks | deposit drives loan | initial deposit, creditworthiness, and profitability | by setting the reserve ratio | initial deposit over reserve ratio | encourage saving, lower the reserve ratio, lower the funding cost |

| credit-generation model | yes, any single private bank can create money | loan drives deposit | creditworthiness, profitability, and capital adequacy ratio | money creation is endogenous and cannot be controlled. CBs can influence it | demand for credit | lower the funding cost, lower the capital adequacy ratio |

Finance Franchise

We learned that the central banks guarantee access to the reserve for the private banks. Why do they do so? At one level, they want to facilitate transactions between private banks, but at a deeper level, it is because private banks can be seen as state agents. It is a public-private partnership.(Hockett and Omarova 2016) It is, or at least supposed to be, a division of labor between the public and private sectors for the social good. In this partnership, the public sector keeps the financial system stable through regulation, supervision, and provision, while the private banking sector efficiently uses its data and expertise to finance creditworthy private agents.

The public sector accommodates the private banking sector in the sense that it provides reserves and cash notes whenever they are needed by the banks. It also monetizes the private banks’ deposits, meaning that we can always convert the bank-created deposits to the state’s money at par and effortlessly. A deposit is a private bank’s liability, and it is accepted by private sector agents because the central bank underwrites it. Thus, the public makes this private banking liability its own liability.

Now we might think about the success of such a partnership. Are the banks really working for our common good? Do they use their state-given power of deposit creation in line with society’s benefit? Do they direct investments towards a sustainable and prosperous future? Is their desire for profit compatible with society’s needs?

References

Footnotes

Let’s overlook the cash notes in circulation for sake of simplicity. They are part of both the money supply and the narrow money.↩︎

The sum of deposits 1000 + 900 + 810↩︎

The bank’s deposit at the central bank↩︎

In general, these limitations are about the business of the bank and are not imposed by any third party.↩︎